What if we looked at the ways players move through an escape room as a type of choreography?

In dance, theater, and film, a choreographer or director helps to create movement patterns for performers, which they rehearse and then perform either live or on camera.

In an escape room, the players are cast in the lead roles, yet there is no rehearsal and no person telling them where to go or how to act. Rather, players’ movements are more subtly guided by the environment and the gameplay.

This type of “choreography” is not a dance number set to music. It’s a physical space that is designed to implicitly encourage certain potential patterns of movement, such as walking toward a spotlight, crawling through a tunnel, or navigating a laser maze. Across these examples and beyond, it’s no revelation that players are physically active in escape rooms, yet there’s an opportunity to consider player choreography far more directly as a designable dimension.

Layers of Movement

When designing around movement, place yourself in the shoes of the player during each scene, puzzle, and story beat as you ask yourself the following questions:

Orientation

How is my body positioned? Am I standing, sitting, crouching, or laying down? Am I looking up, down, or ahead? Are my arms by my sides, outstretched, reaching up, or holding something? Am I in a familiar or uncomfortable pose?

Path

Where does my body move throughout the space? Am I moving in straight or curved lines? Traversing short or long distances? Staying around the perimeter, navigating obstacles, or circling around a large set piece? Traveling new routes or renavigating earlier paths?

Tempo and Tone

Am I walking or running? Excitedly, leisurely, or tentatively? As I enter a new space, do I burst right in or carefully take one step at a time?

Motifs

If I made graphs or heat maps of the preceding categories, plotted against time, what patterns would emerge? Do any particular movement patterns correlate with gameplay mechanics or narrative motifs? For instance, maybe I climb up a ladder or stick my head close to the ground every time I speak to a character. I immediately freeze in place whenever the music or lighting changes a certain way. Or every time a bell rings to indicate a puzzle was solved, I run up some stairs so I don’t miss a recurring video cutscene.

Physical Embodiment

How do my movements make me feel? How do they connect me to the space? Does my tone and quality of movement match what’s happening in the experience around me?

Perspective

In addition to thinking about how and where my body moves, I think of myself as a camera in motion. How do my movements get me to see the space? From what angles and at what speeds? How do my teammates’ bodies and movements look to me?

Image via Escape Blair Witch

How Players Move Through Escape Rooms

Escape rooms already contain many moments of interesting choreography, though they’re often optimized more for gameplay than for the nuances of the movement itself. So, let’s take a look at how some common scenarios might benefit from more intentional choreography.

Laser Mazes

Laser mazes are as common as heist themes, yet I’ve encountered many laser mazes that are designed more around how the lasers look than how the players themselves look and feel while moving through them. These designs often aren’t particularly satisfying to actually traverse, and they end up feeling like a flashy but underdeveloped gimmick. The idea of the interaction overshadows its implementation.

Design laser mazes around being fun, interesting, and aesthetically pleasing to navigate. What are all the possible paths through the lasers? At what points do you have to take more extreme movements, like a belly slide or a high step up? Are these movements strictly required?

Also, ensure that players are well set up to look cool to their teammates, and that the scene lasts long enough to be both seen and experienced by everyone. Do all players have to go through? Do they go through one by one or all at once? If multiple players traverse the maze simultaneously, you could create a slight incline upwards so players in the back can more easily view their teammates ahead, like the inverse of risers in a theater.

Crawling

Tunnels and crawl spaces force players down into a lower vantage point. How can we take advantage of that perspective, especially during the transitions of entering into and exiting from the tunnel? Maybe the tunnel opens up into a much larger space with a lofty set piece. Slightly widen the final stretch of the tunnel so players are able to — and forced to — look up at the new area still from the crouched perspective.

If a tunnel is a portal to a different realm, then its repeated traversal might become a movement motif. Design the tone of that physical transition to match the narrative shift between spaces.

Also consider how physical comfort affects movement. If a tunnel is wide enough and not too painful on the knees, players are more likely to crawl on all fours and stay in the moment, whereas a less comfortable surface, like metal grating, may prompt more awkward and slower movements, which could also be harnessed for a certain effect in the right context.

Cutscenes & Waiting

While watching or listening to a cutscene, players often remain stationary and passive. This can also be the case while waiting for other transitions to finish: a bridge slowly lowers down, a secret compartment rises up, a set piece transforms into something else. In these moments, there’s often an opportunity to keep players more physically engaged and to be aware of exactly how they’re viewing the scene.

Give players an active vantage point while watching a scene play out. Maybe they’re crouched down behind an obstacle, peeking through a window, or looking down on a scene from above. Then finesse the details of their orientation: provide a railing right where you want them to place their hands, or ensure that the window is exactly wide enough so all players have a clear line of sight.

For an audio cutscene, rather than having players awkwardly stand still while listening to a disembodied voice, give them something to look at or touch. Change the lighting in sync with the audio, prompting players where to look — even if that’s as simple as getting them to turn in place. Or even have the voice move throughout the space, and the players follow.

For lengthy transitions, give players more direct control over the action. Rather than having a bridge slowly lower after pressing a button, have the players turn a crank instead. Or rather than having part of the set magically transform in front of the players, design it so that the players are in the center of the action, so that it’s happening because of their actions rather than more passively around them.

The Ritual

Many escape rooms involve arcane rituals, particularly of the supernatural variety. In what’s now become an escape room trope, players join hands and form a circle while chanting some pseudo-Latin text.

Many such rituals feel the same and could benefit from more variation. Pulling inspiration from circle dance traditions, there are a number of ways in which we could change up how players are physically linked. Instead of holding hands, they’re touching fingertips, raising their arms with a particular gesture, or not touching at all.

A circle focuses energy and attention inwards, and it’s often formed around some sort of altar or a sigil on the floor. Does this direct players to look downward? To all place their hands on an object in the center? Or instead of facing inwards, players could form a circle facing outwards as they witness a scene projected on the walls around them.

Also consider the physicality around the act of reading, or more often, the requirements of what surface you’re reading from. I recall one exorcism-themed game where I was mere feet away from an awesome demonic possession, yet I all but missed it because I was tasked with reciting an unnecessarily complex page of text the entire time. In contrast, my teammates remained more positively engaged in their roles of sprinkling holy water and shaking some prayer beads. Keep any text short, memorable, and easy to pronounce so that all players are able to keep their focus outwards, not down on a sheet of paper.

Photo Credit: Zander Fieschko. Models (left to right): Michaela Bulkley, Jessie Wise, Alexis Coria, Karina Guerra.

Movement As A Game Mechanic

Players’ movement needn’t always be just a side effect of the gameplay. It can also function directly as a gameplay input.

Think of a game like red light green light or musical chairs. Playful movement patterns like these can be layered onto other interactions to make them more dynamic. When a player keeps moving after a light changes color or the music stops, the environment reacts to them.

Or, the discovery that your movement is part of a puzzle is the central aha. Perhaps the characters in a video game correspond to your positions around the physical room, or circling around a time machine is what controls time itself.

Follow The Light

Active lighting is one of the most powerful and intuitive ways to guide players around the environment. Like moths drawn to a lamp, it’s a natural instinct to walk toward something that’s illuminated, and to stay still when an area is pitch dark.

Punchdrunk’s Viola’s Room was designed entirely around a “follow the light” mechanic. Each group of audience members was guided through a labyrinthian space by the moving lights around them. At first it felt like a game, yet it quickly became intuitive. It was easy to learn how this movement mechanic applied across different scenarios, whether it be entering through a doorway, walking briskly down a long hallway, or circling around a central set piece.

Image via DarkPark

Many escape rooms, especially in the horror and action genres, also use light as a movement mechanic. For example, DarkPark’s now-closed Stay in the Dark was based around a simple rule: when you were perfectly still and out of direct light, you were functionally invisible to a malevolent character, even if he was looking right at you. So, whenever the music changed and evil approached, you dove into the closest hiding spot shrouded in darkness.

Lighting can also be used to guide players’ attention. When an environment doesn’t clearly signal where players are supposed to look next, they’re prone to aimlessly wander, but dynamic lighting can help. Items that are spotlit are active, and the spotlight turns off or changes color when that interaction has been completed. When players enter a new space, the lighting shows them what threads to pull on first. If a room is dark, you don’t need to return to it at that time.

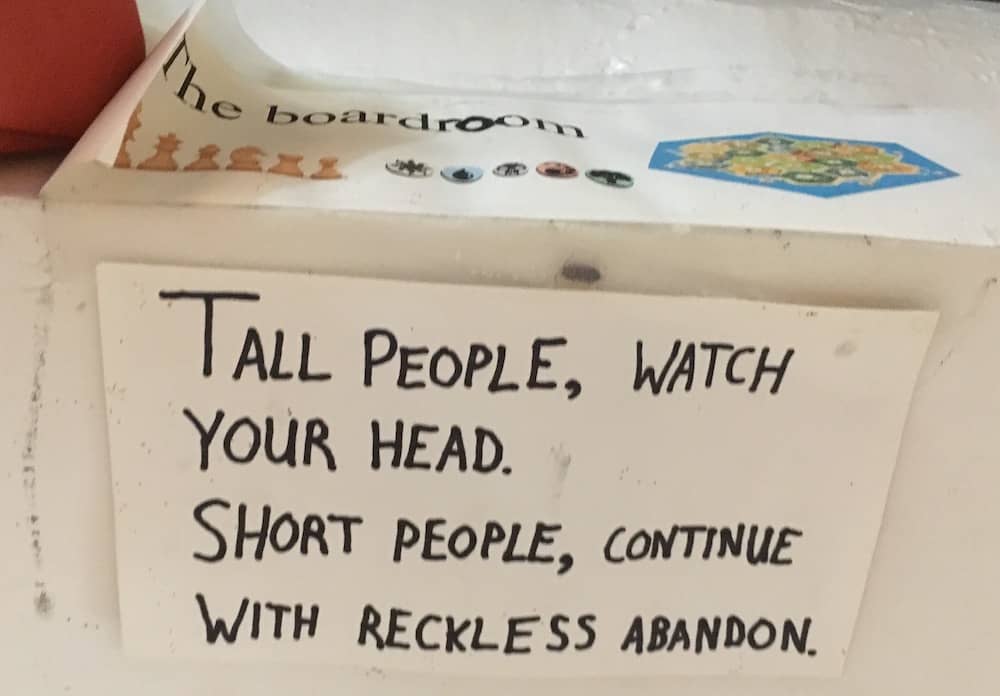

Accessibility

When looking at escape rooms through a lens of movement, we can also consider how that movement adapts to players of varying physical abilities and body types.

At the start of every review we publish on Room Escape Artist, we include some common mobility-oriented accessibility considerations, like whether the game requires crawling, stairs, or tight passages. Not every escape room needs to be for every player, but by clearly communicating this information, we hope to help players make more informed decisions about which games are best suited for them.

Certain accessibility considerations might be fairly obvious, like whether a wheelchair can fit through all areas of the game. But depending on the designer’s background and implicit biases, other considerations might be less obvious, like what situations players must avoid while pregnant or how players who are significantly shorter or taller than average move through the space. (For example, my shorter teammates repeatedly struggled to reach essential puzzle components in Dutch escape rooms, which are designed around tall Dutch people!) Even the classic “2-fingers strength” doesn’t translate well if you’re talking to a rock climber with particularly strong fingers.

Luckily, you have a built-in audience to test all this: your actual players. Watch them, see where certain accessibility-related assumptions might have been wrong, and adapt accordingly. It’s up to you to decide how physically accessible you want your game to be.

Moving Forward

For players to be wholly immersed in an escape room, their movements must match the tone of the space and story.

I can think of numerous escape rooms that were impressive in appearance, but ultimately felt more like a museum than the real thing. While I marveled at the beauty of the space, I never felt like I fully belonged in it. Yet, as soon as an experience organically encourages me out of more neutral movement patterns — by witnessing my teammates moving like action heroes through some obstacles, or kneeling down to listen to a creature in a floor-level burrow, or even ducking down through a low doorway so that I’m forced to look upward in awe as I enter a new space — I more naturally embody my role in the story.

In addition to movement patterns that are guided by the environment and gameplay, which have been the primary focus of this article, actors can also play a pivotal role in guiding players around the space, leading to a perpetual flow state. For an in-depth guide on immersive performance choreography, I highly recommend the book Tandem Dances: Choreographing Immersive Performance by Julia Ritter.

The examples in this article begin to establish a choreographic tool kit specific to escape rooms. By refining existing techniques, learning from adjacent performance disciplines, and increasing our awareness of the many nuanced ways in which players move through immersive environments, we can optimize for meaningful embodiment.

![Cityscape Games – Rockstar [Review]](https://roomescapeartist.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/rockstar-rockstar-3.jpg)

![AdventurEscape – Timescape [Review]](https://roomescapeartist.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/adventurescape-timescape-1.jpg)

![Giddy Box – Month of Date Nights [Review]](https://roomescapeartist.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/date-nights-date-nights-1.jpg)

Leave a Reply