This article is also available in Japanese.

I spent three months diving deep into Japan’s puzzle culture, and what I encountered was nothing short of mindblowing.

Puzzles are everywhere. In the heart of Shinjuku, SCRAP’s Tokyo Mystery Circus is a six-floor “mystery theme park” filled with escape rooms, hall-type games, and a store selling an extensive selection of at-home puzzles and books. Escape cafes like Nanica (Tokyo and Nagoya) and TokiToki (Osaka) offer drinks and snacks alongside puzzle games that get delivered right to your table. Train, metro, and neighborhood puzzle hunts can attract tens of thousands of players monthly, and limited-time events pack stadiums and theme parks.

Puzzles take many forms. Cryptic clothing brand TOKIQIL hosts exclusive pop-ups where attendees must solve puzzles to purchase the items on which they appear. Creators like DAI4KYOKAI (The Fourth Boundary) have pioneered a Japanese ARG renaissance in recent years. Since the 1920s, honkaku mystery novels offer devious narrative logic puzzles, and modern murder mystery games make this style even more interactive. In Hakone, the Karakuri Creation Group crafts intricate mechanical puzzles that range from boxes to whimsical creatures — a creative modern extension of a traditional folk art.

Some puzzles are intended to challenge even the strongest enthusiasts; others welcome families and casual solvers into the fold. I regularly came across light puzzle adventures in all spheres of public life, including parks, museums, castles, stores, and transportation hubs. Typically, even when the difficulty was lower, these puzzles were still well designed to include satisfying ahas — more than just information-collecting scavenger hunts. Puzzles are a popular tool for education, entertainment, and even exercise, as was the case at a Tokyo information center which placed a small puzzle hunt in its stairwell, encouraging visitors to take a healthier alternative to the elevator up to their popular rooftop observation deck.

Seeking Inspiration

During an escape room trip to Spain last year, one of my teammates observed, “Oh, the escape rooms here are the immersive theater!” I had a parallel realization during my time in Japan: the escape rooms in Japan are the puzzle hunts.

Japanese escape rooms are “puzzle performances” where clever, layered, interconnected puzzles set players up to experience hirameki: unforgettable moments of insight and inspiration. In this style, more effort is spent on the puzzle design, rather than on elaborate set design, flashy special effects, or seamless immersion. Even when the physical rooms are on the smaller side, these experiences excel in depth through their gameplay.

This emphasis on puzzles does not mean that Japanese games are inherently devoid of story or emotion. To the contrary, in story-centric games, the story is typically delivered directly through the puzzles, rather than primarily through adjacent experiential elements. Puzzle and narrative ahas are often one and the same.

Additionally, the “one-time use” rule that’s standard in Western escape rooms goes out the door. Any elements introduced earlier in a game may get reused or recombined in later puzzles, often multiple times. It’s common to return to previous puzzles and solve them again in new ways, leading to new answers. This sort of reuse is also central to the final “twists” that Japanese-style games are known for.

Much like Western puzzle hunts, Japanese escape rooms have a steep learning curve. While the majority of each game is still accessible to a general audience, it takes time and experience to properly master the style.

A Grand Mystery

In Japan, nazo is a term that generally refers to anything unknown or unsolved, and is often used to mean a single puzzle. Nazonazo refers to a specific style of riddles or brainteasers, nazotoki describes the “puzzle solving” culture generally, and enthusiasts are referred to as nazokura.

While this style is defined by its constant subversion of players’ expectations, it also fits into a fairly standardized three-act structure:

- ko-nazo (“small puzzle”) – simpler, self-contained warm-up puzzles

- chu-nazo (“medium puzzle”) – medium-difficulty puzzles with more layers and callbacks

- ō-nazo (“big puzzle”) – challenging final puzzle sequence that can function as a structural or narrative metapuzzle

An ō-nazo may require players to recall a specific rule or puzzle mechanic from earlier in the game and reapply it, or zoom out and consider the narrative scenario or even the room’s physical layout from a new perspective. There may be a tiered ending, where a deeper understanding of the scenario can result in a superior outcome. The ō-nazo serves as both capstone and final trial, recontextualizing anything and everything the players have experienced up until that point, tying together the gameplay while also providing a satisfying conclusion to the story or scenario.

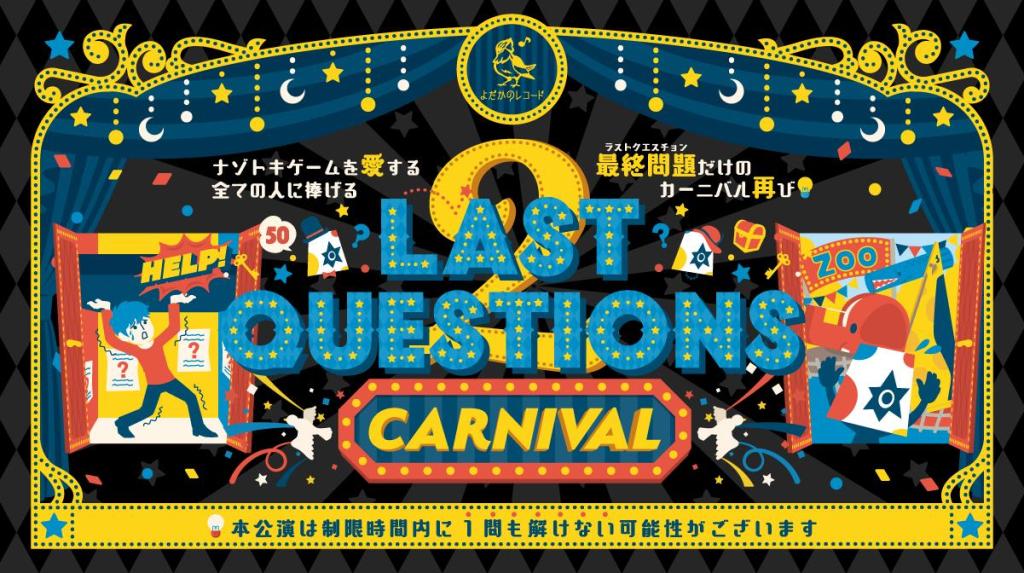

Ō-nazo serves a particular structural function, but it’s also its own distinct puzzle style. This became particularly clear upon attending Yodaka no Record’s ingenious Last Questions 2: Carnival, a hall-type game consisting only of ō-nazo. We were presented with 6 scenarios by 6 different designers, with only 10 minutes to solve each, including the time to read through the story and solutions of the entire fictional game leading up to the last question. This was an event designed exclusively for super-enthusiasts, and it was truly inspirational to witness such a high-concept, experimental event be so well received. Not every game is for every player, but if there’s enough of an audience for groundbreaking work like this, then there’s a solid foundation for continued innovation.

Elegance & Meaningful Failure

Japanese puzzles strive for absolute elegance, insofar as every single design choice and constraint is intentional. A prop might be initially used in a puzzle, but why is that puzzle included at all? Are there any extraneous details that seem redundant, self-evident, or not fully constrained? Is a rule worded to allow for variable interpretation? Pay attention to what you have not fully used yet, and you might just find the final (metaphorical) key to your escape.

There even exists a term for small details that seem ever so slightly off: fukusen, or “foreshadowing.” Astute players will notice these details throughout the game and thus go into the ō-nazo with a sense of which elements are likely to be relevant. Sometimes, the ō-nazo doesn’t even offer any additional puzzle data, instead presenting the entirety of the game up to that point as the final puzzle to be reinterpreted and solved (similar to a “pure meta” in Western puzzle hunts, but without any explicit set of “feeder answers.”)

Even for strong puzzle solvers who know this style well, it’s still common to proceed smoothly through the majority of a game, only to get stuck and fail on the final ō-nazo. This is by design — not setting teams up to fail, but allowing for meaningful failure. Upon running out of time, it’s typical for the game host to walk through the full solution. Much like how Sherlock Holmes reveals the answer to a case where the reader has all the clues but wasn’t able to piece them together, the performance of a puzzle solution can sometimes feel like magic. In certain games, a “revenge ticket” is also available, allowing players to return to retry either the entire game or just the final segment for a discounted price.

Hints are usually provided for all puzzles in a game except for the ō-nazo, not to deprive players of the satisfaction of finishing but because pushing them through the final goalposts would rob them of the opportunity for a fair and unassisted win. With no such safety net, your successes and failures are equally well-earned. In fact, some of my favorite puzzle games in Japan landed so strongly not in spite of failure but because of it. Looking back on exactly why I failed turned a mirror on my own perception, biases, and problem-solving techniques, and in a few cases, it literally shifted how I view the outside world.

In well-designed Japanese puzzle games, the potential for meaningful failure is precisely what provides real emotional stakes.

SCRAP-y by Design

Prior to visiting Japan, I was only familiar with one Japanese escape room company: SCRAP. Founded in 2007, SCRAP was the very first real-life escape room globally, and nearly two decades later, they are still the largest company in Japan.

However, unlike many other early-days escape room companies that rely on their first-to-market advantages and still offer experiences that have changed little in the past decade, SCRAP has continued to evolve at a speed that is hard to comprehend. They employ dozens of full-time puzzle designers, and release hundreds of new titles each year across a range of formats. This level of output and innovation is sustained by a proportionately massive fanbase, which is constantly expanding with the help of regular collaborations with well-known IPs, events hosted in conjunction with major theme parks, sports stadiums, and transit systems, and a strong presence in many Japanese bookstores.

SCRAP’s current designs are multiple generations beyond those at their former United States locations in the 2010s. In my personal experience playing all of SCRAP’s current English-language and many of their Japanese-only offerings, their gameplay was difficult but consistently fair. Even when we failed a game, the endings were creative and satisfying. We could look back and think “we should have gotten that!” rather than “we never would have gotten that!” As we played more examples of SCRAP’s style, we learned common tropes and patterns, as well as what to look out for and how to best manage our time.

SCRAP’s style is a skill to be practiced and improved. Early failures ultimately lead to more meaningful successes.

Beyond SCRAP

During my time in Japan, I quickly learned that SCRAP was far from the only puzzle company, and I was fortunate to experience additional games by Tumbleweed, Yodaka no Record, Nanica, Riddler, XEOXY, Kaerimichi Kobo, TokiToki escape cafe, and The Nazo Stand. While the market as a whole has clearly been influenced by SCRAP, each of these companies has their own distinctive style, unique charm, and dedicated fanbase.

To note, beyond the official English offerings at SCRAP, the overwhelming majority of this market is inaccessible to non-Japanese speakers, and I was only able to dive deeper into this culture with the generous assistance of some local enthusiasts and designers, along with regular translation assistance from Google Lens and ChatGPT.

Community & Connection at the Nazotoki Market

While visiting many of these companies, I kept seeing flyers for an event called the Nazotoki Market. On November 9, 2025, I paid a visit to Tokyo Dome City’s massive Prism Hall for this enigmatic expo showcasing over 70 different Japanese puzzle companies, each selling their at-home games.

Organized and sponsored by SCRAP, the Nazotoki Market was the first event of its kind in bringing together creators both large and small. Right alongside the biggest booths — SCRAP, Riddler, Tumbleweed, TOKIQIL, Yodaka no Record, and Machihack — were newer companies, independent creators, and university puzzle clubs. Some of these companies run escape rooms at their own venues, festivals, or pop-up events; others focus just on creating at-home games. Everyone, it seemed, was welcome, and the environment was overwhelmingly enthusiastic and supportive.

For our North American audience, this event felt something like a PAX Unplugged, but where every booth was a cross between PostCurious and an MIT Mystery Hunt team.

Within minutes of arriving at the Nazotoki Market, I found myself unexpectedly tearing up. Wherever I turned, I witnessed a patchwork of intensely nerdy passions. Attendees who had lined up in the rain long before doors opened all rushed in to buy their favorite company’s hot new release, and then lined up again just to have the game’s creator sign it. Fans of Riddler’s popular YouTube channel took photos on a recreation of Riddler’s iconic streaming setup. Yodaka’s lampshade-esque mascot roamed the hall, posing occasionally with adoring puzzlers. TOKIQIL’s gallery of puzzle shirts was constantly packed with puzzlers; many already wore TOKIQIL’s attire throughout the event, and I quickly joined their ranks. Some booths presented particularly absurd or whimsical creations, from one whose puzzles use only the character あ to another with puzzles that all solve to the word ひげ (hige, mustache or beard). University students offered an impressive selection of their original designs, all while also collaborating with and eyeing potential jobs at established puzzle companies, many of which are included alumni from those same universities.

Such an intricate ecosystem and strong sense of comradeship around puzzles signals an incredibly bright future for Japanese nazotoki culture. Yes, Japanese puzzle designs are remarkably clever and elegant, but perhaps the true brilliance lies in the unique forms of human connection that these puzzles facilitate.

Related Articles

This article only scratches the surface of the Japanese puzzle industry. To learn more, check out:

- Tips on playing Japanese escape rooms as a foreigner by REA Contributor Ryan Brady

- Reviews of Japanese escape rooms currently available in English (coming soon!)

- Tips for succeeding in Japanese escape rooms (coming soon!)

- A Conversation with SCRAP on their Approach, Cultural Differences, and Adaptation

- What Escape Rooms Can Learn from Puzzle Hunts

![Red Door Escape Room San Mateo – Fair Game [Review]](https://roomescapeartist.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/fair-game-fair-game-1.jpg)

![The Escape Game – Only Murders in the Building (Season 3/4) [Review]](https://roomescapeartist.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-escape-game-only-murders-in-the-building-2.jpg)

Leave a Reply